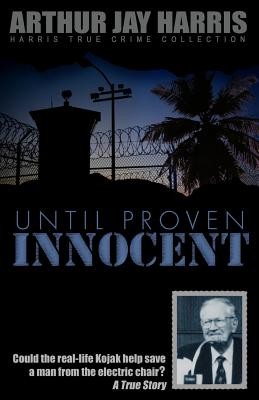

| Until Proven Innocent: Could the real-life Kojak help save a man from the electric chair? Contributor(s): Harris, Arthur Jay (Author) |

|

|

ISBN: 1484092449 ISBN-13: 9781484092446 Publisher: Createspace Independent Publishing Platform OUR PRICE: $18.00 Product Type: Paperback - Other Formats Published: June 2013 |

| Additional Information |

| BISAC Categories: - True Crime | Murder - Serial Killers - Social Science | Criminology |

| Series: Harris True Crime Collection |

| Physical Information: 1.02" H x 5.5" W x 8.5" (1.28 lbs) 460 pages |

| Descriptions, Reviews, Etc. |

| Publisher Description: Three years into the investigation of a horrific homicide case, a suburban home invasion murder of a wife and mother and point-blank shootings of her infant, husband, and father-in-law, the prosecutor slowly realizes that he and the police have been totally wrong about one of his capital murder defendants and reverses course. Story seen on the series True Convictions on Investigative Discovery, in January 2018. Until Proven Innocent was originally published by Avon Books. Breathless, a woman's call to 911 interrupted a quiet night in the horse country suburbs: "I'm stabbed to death. Please " Did somebody stab you? asked the operator. "Yes And my husband, my baby " Within minutes, officers arrived at her remote ranch house but didn't know whether an assailant was still present. Announcing themselves, they got no response, then entered anyway, guns drawn, and began a dangerous, tense search, room by room. Then they heard a baby's scream. Although the house wasn't yet fully cleared, they followed the wailing to the master bedroom where they found, tied and gagged, her husband and elderly father-in-law. They and their 18-month-old all had been shot point-blank in the head-but were still alive. Shocked, the officers called out to bring in paramedics, who had to crawl through the living room because the house still had not been completely cleared. Hurrying, and contrary to usual procedures, the officers spread out. One found a locked closet door; four officers gathered, and with guns ready, one of them kicked it in. Behind it they found their 911 caller-still holding the phone. "Oh, shit," said the kicker. In the history of Davie, Florida, there had never been such a savage and sociopathic crime, and police and homicide prosecutor Brian Cavanagh were determined to resolve it. For three years, they had two suspects under surveillance, then arrest. Both faced the death penalty. But as the legal case progressed, Cavanagh began to doubt that the defendants were partners. Possibly one had been a victim of the other, as well. In 1963, Cavanagh's dad, Tom, a Manhattan lieutenant of detectives, had a famous case called the "Career Girls Murder," two women in their twenties found horribly mutilated in their Upper East Side apartment. The newspapers played the story big, a random killer on the loose, meanwhile Tom and his precinct detectives had been unable to solve it. Months after the murder, Brooklyn detectives declared the case solved; they'd taken a signed confession from a man with a low IQ. Their additional proof was a photo in his wallet; it was of one of the girls he killed, he said. The man quickly recanted, although that didn't much matter to the Brooklyn detectives. As soon as he heard some of the details of the confession, Tom disbelieved it; the man didn't fit the profile. Needing to work quietly under the most difficult of circumstances, Tom sent out his own detectives to do the impossible: identify the girl in the picture. When they found her, she asked, "Where did you get that?" After all that impossibly good work, Tom and his detectives caught a break and found the real killer of the Career Girls. Until then, Tom said, he hadn't believed that police could make such mistakes. Afterward, as a result, New York State outlawed the death penalty. As well, this remarkable story inspired a TV movie and series starring a character playing Cavanagh's role. His name was Lt. Theo Kojak. As a child, Brian Cavanagh had watched his dad's anguish throughout that situation. Now, he had a case that was remarkably similar-except that he was potentially on the wrong side. Once his confidence level in the guilt of one of his defendants dropped to a level of precarious uncertainty, Brian showed the same courage as did his dad so many years earlier-proving that the son was the equal of his father. |